armscye

One of the Regulars

- Messages

- 143

- Location

- New England

Several Loungers have asked if I can document the process I use for reconditioning leather jackets, which involves the unusual steps of machine washing, tumbling, and some unusual conditioning steps. Recently my flea market hauntings turned up a suitable candidate jacket, and so I am pleased to provide this tutorial.

Let me begin with the standard internet caveat YMMV, meaning that your mileage may vary. I have washed more than thirty flight and moto jackets over the past five years, without destroying one, so I am confident that it is not a destructive process for hard finished decent quality jackets. I have also used the process with suede, nubuck, and pigskin, but only with the additional step of washing the jacket in a mesh bag. And I've dealt with some weak linings and fraying seams that may have been exacerbated by washing, but the need for such repairs is not uncommon in any vintage leather.

My jacket candidate for this project turned up in central Connecticut on a fine Sunday morning. It appears to be well made private label jacket, in the style of the old Buco J100-- shirt styling, two zipped breast pockets, central zipper, a snug fit, and a light quilted lining with zip sleeves. I say private label because the supplied label does not define brand, and looks like it is intended to be displayed with a retailer's companion label adjacent. The jacket is almost certainly US made (Talon brass zippers, US rivets, no import tags, one-piece back) in a midweight cowhide that looks to have been sprayed after chrome tanning (the leather is uncolored at it center). My guess as to history is that it is a piece from the Seventies “On any Sunday” era, maybe made by Brooks, Beck, Reed, Excelled, or similar.

Here is the “Before” shot—thirty years worth of road grit and grime have matted the leather, leaving it with some nice patina, but also that flat, dull look.

As my Step One, after inspecting the jacket for structural issues that washing might exacerbate, I start by zipping the jacket, and buckling all buckles and snaps. The goal is to retain as much structural integrity as possible, to keep the general shape from being twisted, and to prevent unfastened metal fittings from puncturing the hide.

I use a FRONT LOAD washer exclusively. Without an agitator column that the jacket would wrap around, this type of washer is vastly more gentle on heavy items, and tends to do a better job of rinsing as well.

I have experimented with top load washers, but they are a poor second choice—you can get by placing the jacket in a mesh bag to prevent it from wrapping around the column, and then being twisted and torn (I lost a nice security-style nylon jacket this way once). But you won’t get the cleaning power of a front loader.

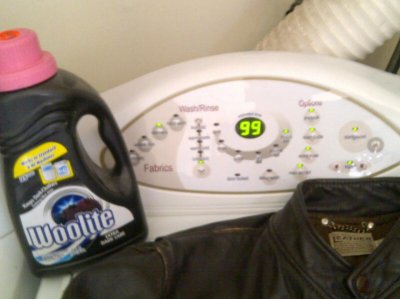

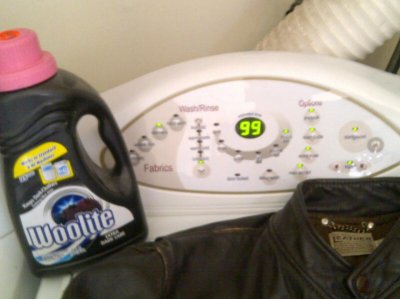

In Step Two, I then add a normal washload measure of Woolite. I use the colorfast Woolite in the black bottle, in order to prevent unwanted bleaching effects. On rare occasions, when dealing with a heavily oiled or very dirty jacket, I’ve switched to a half measure of conventional liquid detergent. But this generally strips almost all of the oils (the wash water looks like a milkshake), and leaves a much duller finish. There is also a fairly dramatic effect on the amount of restorative oil the jacket will subsequently drink up: a conventional detergent really dries the leather. I wash cold, usually using the delicates cycle to limit the amount of tumbling.

99 minutes later, I remove the jacket by cradling from below and lifting it. Remember, a wet jacket has lost much of its strength, at the exact moment it has quadrupled its weight.

I then place the jacket on a table, and gently shift it onto a sturdy, heavily padded hanger. I use wooden suit hangers padded with kid’s foam pool noodles. At this point, the wet hide will look fabulous-- thick and puffy at the seams because of the water— like an old Schott horsehide Perfecto.

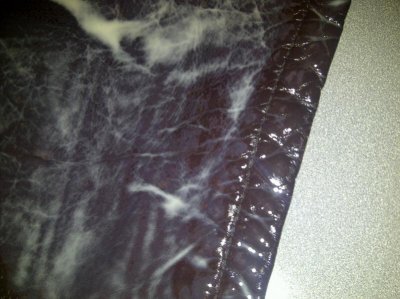

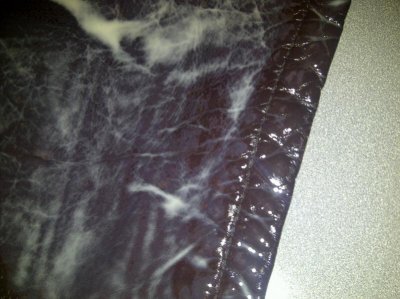

As an aside, I believe that the washing process has several positive effects that collectively transform the jacket. Washing removes the matted effect, thickening the hide the same way a kitchen sponge gets fatter when wet. It gets rid of all the grit that is dulling the finish and hiding the grain. It accents the hide striations. And it often tightens the stitching a bit, creating interesting puckering and patination at the seams.

As Step Three, I let the jacket dry a day, then very gently turn it inside out and let dry a second day, pulling out any pocket linings. This drying phase, by the way, is the proper time to shape the collar to any drape you like. My Cooper A2 collar looked ridiculous until I reshaped it while wet—now it has a great “Twelve o Clock High” military curl.

In Step Four, here’s the Big Reveal of my secret conditioning technique. I’ve experimented for years with essentially every leather conditioning compound out there, including but not limited to Sno Seal, Mink Oil, Pecard’s, Obenauf’s, Kiwi Leather lotion, various neatsfoot oils, and Urad. I’ve also talked to tanners, shoe repairmen, chemists, and the engineers at Audi (a client) who specify their interior leather. After all this research, and a couple of hundred experiments, I’ve circled back around to plain ol’ Lexol as providing the correct combination of penetration, softening, and visual benefit.

Here’s the short version of why: leather is basically spaghetti strands made of protein, lightly glued together with more protein, but then lubricated for flexibility by animal fats so the strands can slide over one another. When you tan leather, you remove most of the animal fats (since they decay over time) with a caustic tanning solution, winding up with what look like sheets of white or blue cardboard. Then, in a process tanneries call Fat Liquoring, you replace the lost animal fats with lubricants that won’t decay. Real tanneries tumble hides in heated solutions of oils that are emulsified with water to aid penetration into the hide. And Lexol is exactly that—an oil emulsified in a water base.

In my system, I lay the jacket out on a table (important— vertical hanging lets the Lexol run off), and then paint on 2-3 coats of Lexol at 4 hour intervals, each heated to steaming in the microwave. The heat seems to help the Lexol penetrate, and I begin to see grain enhancement within minutes after applying it. I have not, by the way, ever experienced Lexol soak through to the lining on any quality jacket—though it happened once with a thin pigskin mall jacket.

When the hide still dries to a gloss after a full day, I know I’ve stuffed as much oil into the leather as it is going to take. At this point, the jacket looks like a $29 vinyl item, but don’t panic. We’re going to undo that overglossed condition in the next steps.

In Step Five, I use several measures to get rid of the excess oil. The first step is to wipe the jacket down fairly vigorously with a damp cloth, turning frequently. You’ll see some color come out of the leather, even with a vintage jacket, but that’s normal. Then I zip everything back up, walk back to the laundry room, and put the jacket in the dryer—set to tumble WITH NO HEAT. I use about ten plastic dryer balls—nubbed plastic balls that are Europe’s alternative to fabric softener—and tumble the jacket for about an hour. I do not recommend tennis balls, since I’ve found their nap seems to absorb a lot of oil.

The tumbling softens the leather, beats the oil into the interior of the leather gently, and redistributes any areas that are overoiled. It also can leave the interior of the dryer very slightly oil, but I take of that by tumbling a towel for a few minutes afterward.

One more damp cloth wipedown, with special attention to crevices, and the jacket should look supple, with that satiny expensive-leather look, and a tactile “hand” that feels amazing.

Let me begin with the standard internet caveat YMMV, meaning that your mileage may vary. I have washed more than thirty flight and moto jackets over the past five years, without destroying one, so I am confident that it is not a destructive process for hard finished decent quality jackets. I have also used the process with suede, nubuck, and pigskin, but only with the additional step of washing the jacket in a mesh bag. And I've dealt with some weak linings and fraying seams that may have been exacerbated by washing, but the need for such repairs is not uncommon in any vintage leather.

My jacket candidate for this project turned up in central Connecticut on a fine Sunday morning. It appears to be well made private label jacket, in the style of the old Buco J100-- shirt styling, two zipped breast pockets, central zipper, a snug fit, and a light quilted lining with zip sleeves. I say private label because the supplied label does not define brand, and looks like it is intended to be displayed with a retailer's companion label adjacent. The jacket is almost certainly US made (Talon brass zippers, US rivets, no import tags, one-piece back) in a midweight cowhide that looks to have been sprayed after chrome tanning (the leather is uncolored at it center). My guess as to history is that it is a piece from the Seventies “On any Sunday” era, maybe made by Brooks, Beck, Reed, Excelled, or similar.

Here is the “Before” shot—thirty years worth of road grit and grime have matted the leather, leaving it with some nice patina, but also that flat, dull look.

As my Step One, after inspecting the jacket for structural issues that washing might exacerbate, I start by zipping the jacket, and buckling all buckles and snaps. The goal is to retain as much structural integrity as possible, to keep the general shape from being twisted, and to prevent unfastened metal fittings from puncturing the hide.

I use a FRONT LOAD washer exclusively. Without an agitator column that the jacket would wrap around, this type of washer is vastly more gentle on heavy items, and tends to do a better job of rinsing as well.

I have experimented with top load washers, but they are a poor second choice—you can get by placing the jacket in a mesh bag to prevent it from wrapping around the column, and then being twisted and torn (I lost a nice security-style nylon jacket this way once). But you won’t get the cleaning power of a front loader.

In Step Two, I then add a normal washload measure of Woolite. I use the colorfast Woolite in the black bottle, in order to prevent unwanted bleaching effects. On rare occasions, when dealing with a heavily oiled or very dirty jacket, I’ve switched to a half measure of conventional liquid detergent. But this generally strips almost all of the oils (the wash water looks like a milkshake), and leaves a much duller finish. There is also a fairly dramatic effect on the amount of restorative oil the jacket will subsequently drink up: a conventional detergent really dries the leather. I wash cold, usually using the delicates cycle to limit the amount of tumbling.

99 minutes later, I remove the jacket by cradling from below and lifting it. Remember, a wet jacket has lost much of its strength, at the exact moment it has quadrupled its weight.

I then place the jacket on a table, and gently shift it onto a sturdy, heavily padded hanger. I use wooden suit hangers padded with kid’s foam pool noodles. At this point, the wet hide will look fabulous-- thick and puffy at the seams because of the water— like an old Schott horsehide Perfecto.

As an aside, I believe that the washing process has several positive effects that collectively transform the jacket. Washing removes the matted effect, thickening the hide the same way a kitchen sponge gets fatter when wet. It gets rid of all the grit that is dulling the finish and hiding the grain. It accents the hide striations. And it often tightens the stitching a bit, creating interesting puckering and patination at the seams.

As Step Three, I let the jacket dry a day, then very gently turn it inside out and let dry a second day, pulling out any pocket linings. This drying phase, by the way, is the proper time to shape the collar to any drape you like. My Cooper A2 collar looked ridiculous until I reshaped it while wet—now it has a great “Twelve o Clock High” military curl.

In Step Four, here’s the Big Reveal of my secret conditioning technique. I’ve experimented for years with essentially every leather conditioning compound out there, including but not limited to Sno Seal, Mink Oil, Pecard’s, Obenauf’s, Kiwi Leather lotion, various neatsfoot oils, and Urad. I’ve also talked to tanners, shoe repairmen, chemists, and the engineers at Audi (a client) who specify their interior leather. After all this research, and a couple of hundred experiments, I’ve circled back around to plain ol’ Lexol as providing the correct combination of penetration, softening, and visual benefit.

Here’s the short version of why: leather is basically spaghetti strands made of protein, lightly glued together with more protein, but then lubricated for flexibility by animal fats so the strands can slide over one another. When you tan leather, you remove most of the animal fats (since they decay over time) with a caustic tanning solution, winding up with what look like sheets of white or blue cardboard. Then, in a process tanneries call Fat Liquoring, you replace the lost animal fats with lubricants that won’t decay. Real tanneries tumble hides in heated solutions of oils that are emulsified with water to aid penetration into the hide. And Lexol is exactly that—an oil emulsified in a water base.

In my system, I lay the jacket out on a table (important— vertical hanging lets the Lexol run off), and then paint on 2-3 coats of Lexol at 4 hour intervals, each heated to steaming in the microwave. The heat seems to help the Lexol penetrate, and I begin to see grain enhancement within minutes after applying it. I have not, by the way, ever experienced Lexol soak through to the lining on any quality jacket—though it happened once with a thin pigskin mall jacket.

When the hide still dries to a gloss after a full day, I know I’ve stuffed as much oil into the leather as it is going to take. At this point, the jacket looks like a $29 vinyl item, but don’t panic. We’re going to undo that overglossed condition in the next steps.

In Step Five, I use several measures to get rid of the excess oil. The first step is to wipe the jacket down fairly vigorously with a damp cloth, turning frequently. You’ll see some color come out of the leather, even with a vintage jacket, but that’s normal. Then I zip everything back up, walk back to the laundry room, and put the jacket in the dryer—set to tumble WITH NO HEAT. I use about ten plastic dryer balls—nubbed plastic balls that are Europe’s alternative to fabric softener—and tumble the jacket for about an hour. I do not recommend tennis balls, since I’ve found their nap seems to absorb a lot of oil.

The tumbling softens the leather, beats the oil into the interior of the leather gently, and redistributes any areas that are overoiled. It also can leave the interior of the dryer very slightly oil, but I take of that by tumbling a towel for a few minutes afterward.

One more damp cloth wipedown, with special attention to crevices, and the jacket should look supple, with that satiny expensive-leather look, and a tactile “hand” that feels amazing.