Midnight Palace

Vendor

- Messages

- 640

- Location

- Hollywood, CA

Hope you guys enjoy it

Femme Fatale: The Black Widow of Film Noir

She was a predator; she was the antagonist. There was nothing honorable about her, from her selfish thoughts to her shameless actions. She came into view with a purpose and left victims in her wake; they were the spoils of her crusade for personal gain. She was a woman with venom so toxic that the most intrepid male would be rendered helpless in her grip. She was the femme fatale.

Film Noir, as a whole, was largely the product of a demoralized country. American soldiers who’d fought in the war were thrust into a different world as they returned home. Rather than receiving a hero’s welcome, they found life had belittled them in their absence. Many of their wives had been unfaithful and their employers no longer held a position for them. They had survived the horrific nature of battle and again found themselves in the company of chaos. The effect on these bewildered men would be painted in strips of black and white across the screen. Borrowing elements of German Expressionism, such as stark lighting and contrasts (as seen in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), filmmakers presented a society that had been beaten into madness. With the apparent deadliness of the female lead in Films Noir, there was little speculation as to who was thought the cause of it all.

The mother of all Films Noir is 1944’s Double Indemnity, with Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck. It wasn’t, however, the first. 1941’s The Maltese Falcon is generally considered our first step into cinematic darkness. The United States was still in the middle of World War II, and the majority of sons, brothers and husbands were away. Many believe noir filmmakers to have opposed the war entirely, releasing their cramped aggression towards the country’s decision-makers through their work. That would certainly make sense and explain the noir style surfacing before war’s end. However, the most interesting element is the portrayal of a “spider-woman” so early in the game. If symbolism is any guide, one could surmise that a poisonous female was the representation of life in general. In an era headlined by things out of everyday man’s control, the term “life’s a ____” takes on a new meaning. In creating this heartless woman, noir reversed the stereotype of a weaker sex and propelled her into a newfound iciness.

The plot of Double Indemnity was not nearly as complex as the mind of Phyllis Dietrichson (Stanwyck). It was actually simple and straight-forward. Dietrichson recruits insurance salesman Water Neff (MacMurray) to assist her in murdering her husband for the insurance money. The iconic value of this film belongs to its ruthlessness. The film world would see a similar plot two years later with The Postman Always Rings Twice, but Cora Smith (Lana Turner) wasn‚Äôt as blas?© as Phyllis Dietrichson about murder. In addition to the character, there was a blatant physical dissimilarity. Dietrichson had cheap-looking blonde hair. It added another level to her superficiality and subtracted another layer from her virtue, which she appeared to enjoy.

The role of the femme fatale was to obtain, by any means, her darkest desires. She rarely held an ordinary job, but rather worked full-time as a deceptive siren. Sex was her most valuable asset, the prospect of which blindfolded the male conscience while she lured him into an unavoidable web. Such was the case in Sunset Boulevard. Joe Gillis (William Holden) is a struggling screenwriter held captive by a delusional, forgotten silent film star (‘Norma Desmond’ played by Gloria Swanson). Gillis hopes to revive his own fading career by proofreading the script of Desmond’s “comeback” movie. Unbeknownst to him, she resurrects her glory days through his youthfulness; however, it’s painfully obvious that she’ll never return to Hollywood’s circle of the elite. Desmond has little reason to exist if not for the glorification of her ego and Gillis is nothing if not successful. While Gillis believes he has no physical attraction to the aging actress, there is a subtle undertone of needing an experienced woman. He hasn’t been imprisoned; in fact, he freely departs at night and returns of his own will despite Desmond’s eccentricities. The only trap is a burgeoning mental stronghold.

In 1949’s Gun Crazy, Peggy Cummings plays Annie Starr, a sharp shooting carnival performer with a lust for violence. John Dall is Bart Tare, himself an ace triggerman who uses his talent for sport. Once paired with Starr, his morals are stolen and recycled into those of a crazed criminal. Tare is merely a pawn whose personal views are disregarded for the benefit of Starr’s maniacal plans. His innocent abilities become a foretelling of downfall. This is stereotypical of the femme fatale’s modus operandi. Gun Crazy has a fitting alternate title of Deadly is the Female.

The leading lady of noir was not always deliberately evil. Gilda is a much celebrated noir from 1946 that teetered on the threshold of intention and circumstance. Rita Hayworth plays the title character, and while she is the catalyst for much of the film’s negativity, the audience can’t help but feel some level of sorrow for her. She appears to be made of two different women, one who can handle herself and the other a frightened child with no sense of direction. Gilda is a case of backfire in some regards. Filmmakers who intended to kick dirt on the principles of women may have done so without consideration for the end result. For example, when historians analyze Gilda, they remember it primarily for Rita Hayworth’s performance. They are prone to memorize the words to “Put the Blame on Mame” rather than focus on any male victims in the film. Men will still be men. Granted, the primal nature of the male hormones is what makes them an easy target for the prowling femme; though, it causes the male audience to miss the point. Female moviegoers are more likely to be insulted and appalled.

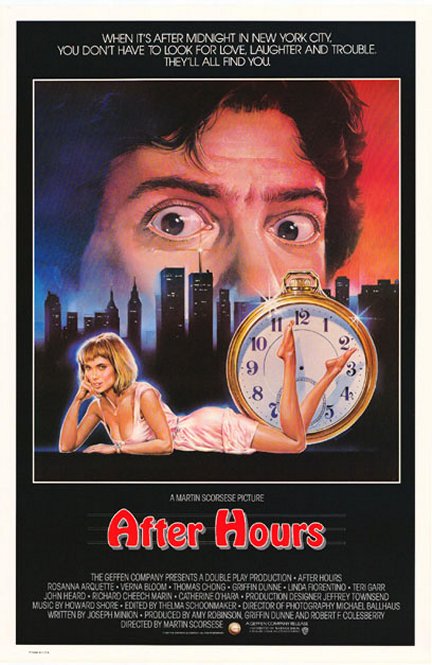

In later years, neo noir became the echo of the 1940s. Martin Scorcese’s After Hours, released in 1985, is a stunning example of revamping noir’s paranoid yesterdays. Griffin Dunne plays a man trapped in the maze of New York City, constantly pursued by unstable women who eventually try to harm him in some fashion. The film is shot almost entirely at night, adding the ambiance of unseen forces at work. Scorcese also used quirky camera angles, including one shot of Dunne busting through a door, as seen from overhead. Camera angles were another characteristic of film noir. They served to isolate and confine the subject to a single frame. This, coupled with the trap of the cold-blooded female, left no way out. That is the ultimate definition of the black widow; she left no way out.

The femme fatale lived in her own sinister town, one without law enforcement or confessions. There were no consequences for bad judgment or penalties for crime. She strolled along the city streets under a dim lamp. While she has worn the face of many actresses over the years, her shadowed personality has never wavered. On film, she has achieved the immortality of a non-human entity. Perhaps that was the final goal of the filmmakers – to create a woman whose wickedness would transcend the passing decades.

Femme Fatale: The Black Widow of Film Noir

She was a predator; she was the antagonist. There was nothing honorable about her, from her selfish thoughts to her shameless actions. She came into view with a purpose and left victims in her wake; they were the spoils of her crusade for personal gain. She was a woman with venom so toxic that the most intrepid male would be rendered helpless in her grip. She was the femme fatale.

Film Noir, as a whole, was largely the product of a demoralized country. American soldiers who’d fought in the war were thrust into a different world as they returned home. Rather than receiving a hero’s welcome, they found life had belittled them in their absence. Many of their wives had been unfaithful and their employers no longer held a position for them. They had survived the horrific nature of battle and again found themselves in the company of chaos. The effect on these bewildered men would be painted in strips of black and white across the screen. Borrowing elements of German Expressionism, such as stark lighting and contrasts (as seen in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), filmmakers presented a society that had been beaten into madness. With the apparent deadliness of the female lead in Films Noir, there was little speculation as to who was thought the cause of it all.

The mother of all Films Noir is 1944’s Double Indemnity, with Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck. It wasn’t, however, the first. 1941’s The Maltese Falcon is generally considered our first step into cinematic darkness. The United States was still in the middle of World War II, and the majority of sons, brothers and husbands were away. Many believe noir filmmakers to have opposed the war entirely, releasing their cramped aggression towards the country’s decision-makers through their work. That would certainly make sense and explain the noir style surfacing before war’s end. However, the most interesting element is the portrayal of a “spider-woman” so early in the game. If symbolism is any guide, one could surmise that a poisonous female was the representation of life in general. In an era headlined by things out of everyday man’s control, the term “life’s a ____” takes on a new meaning. In creating this heartless woman, noir reversed the stereotype of a weaker sex and propelled her into a newfound iciness.

The plot of Double Indemnity was not nearly as complex as the mind of Phyllis Dietrichson (Stanwyck). It was actually simple and straight-forward. Dietrichson recruits insurance salesman Water Neff (MacMurray) to assist her in murdering her husband for the insurance money. The iconic value of this film belongs to its ruthlessness. The film world would see a similar plot two years later with The Postman Always Rings Twice, but Cora Smith (Lana Turner) wasn‚Äôt as blas?© as Phyllis Dietrichson about murder. In addition to the character, there was a blatant physical dissimilarity. Dietrichson had cheap-looking blonde hair. It added another level to her superficiality and subtracted another layer from her virtue, which she appeared to enjoy.

The role of the femme fatale was to obtain, by any means, her darkest desires. She rarely held an ordinary job, but rather worked full-time as a deceptive siren. Sex was her most valuable asset, the prospect of which blindfolded the male conscience while she lured him into an unavoidable web. Such was the case in Sunset Boulevard. Joe Gillis (William Holden) is a struggling screenwriter held captive by a delusional, forgotten silent film star (‘Norma Desmond’ played by Gloria Swanson). Gillis hopes to revive his own fading career by proofreading the script of Desmond’s “comeback” movie. Unbeknownst to him, she resurrects her glory days through his youthfulness; however, it’s painfully obvious that she’ll never return to Hollywood’s circle of the elite. Desmond has little reason to exist if not for the glorification of her ego and Gillis is nothing if not successful. While Gillis believes he has no physical attraction to the aging actress, there is a subtle undertone of needing an experienced woman. He hasn’t been imprisoned; in fact, he freely departs at night and returns of his own will despite Desmond’s eccentricities. The only trap is a burgeoning mental stronghold.

In 1949’s Gun Crazy, Peggy Cummings plays Annie Starr, a sharp shooting carnival performer with a lust for violence. John Dall is Bart Tare, himself an ace triggerman who uses his talent for sport. Once paired with Starr, his morals are stolen and recycled into those of a crazed criminal. Tare is merely a pawn whose personal views are disregarded for the benefit of Starr’s maniacal plans. His innocent abilities become a foretelling of downfall. This is stereotypical of the femme fatale’s modus operandi. Gun Crazy has a fitting alternate title of Deadly is the Female.

The leading lady of noir was not always deliberately evil. Gilda is a much celebrated noir from 1946 that teetered on the threshold of intention and circumstance. Rita Hayworth plays the title character, and while she is the catalyst for much of the film’s negativity, the audience can’t help but feel some level of sorrow for her. She appears to be made of two different women, one who can handle herself and the other a frightened child with no sense of direction. Gilda is a case of backfire in some regards. Filmmakers who intended to kick dirt on the principles of women may have done so without consideration for the end result. For example, when historians analyze Gilda, they remember it primarily for Rita Hayworth’s performance. They are prone to memorize the words to “Put the Blame on Mame” rather than focus on any male victims in the film. Men will still be men. Granted, the primal nature of the male hormones is what makes them an easy target for the prowling femme; though, it causes the male audience to miss the point. Female moviegoers are more likely to be insulted and appalled.

In later years, neo noir became the echo of the 1940s. Martin Scorcese’s After Hours, released in 1985, is a stunning example of revamping noir’s paranoid yesterdays. Griffin Dunne plays a man trapped in the maze of New York City, constantly pursued by unstable women who eventually try to harm him in some fashion. The film is shot almost entirely at night, adding the ambiance of unseen forces at work. Scorcese also used quirky camera angles, including one shot of Dunne busting through a door, as seen from overhead. Camera angles were another characteristic of film noir. They served to isolate and confine the subject to a single frame. This, coupled with the trap of the cold-blooded female, left no way out. That is the ultimate definition of the black widow; she left no way out.

The femme fatale lived in her own sinister town, one without law enforcement or confessions. There were no consequences for bad judgment or penalties for crime. She strolled along the city streets under a dim lamp. While she has worn the face of many actresses over the years, her shadowed personality has never wavered. On film, she has achieved the immortality of a non-human entity. Perhaps that was the final goal of the filmmakers – to create a woman whose wickedness would transcend the passing decades.